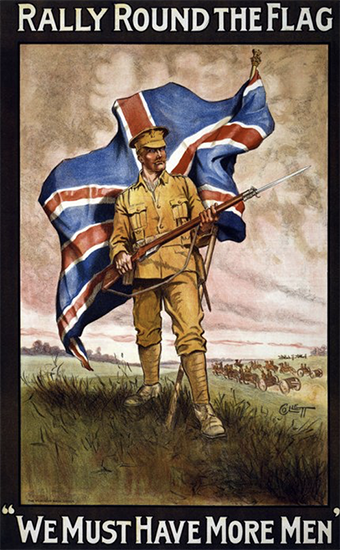

The Western Front—1917. Barbed wire and waist deep mud. Artillery and mustard gas. Machine guns and snipers. Above the abyss, British BE2s and Sopwith Pups struggle to hold their own against the German Albatrosses.

The air war slowly turns with the arrival of the Sopwith Camel, the SE5, and the Bristol Fighter. In the east, the Bolsheviks sign an armistice with Germany, freeing up fifty German divisions. Ludendorff launches a series of massive attacks on the Western Front in the spring of 1918, but the Americans are arriving in strength and the Allies hold. Spearheaded by 500 tanks, the Allies counterattack near Amiens in August—the beginning of the Hundred Days Offensive that will end the war.

CHANGES WROUGHT takes us into the cockpits of Britain’s Royal Flying Corps above World War One’s Western Front; from a hospital in Yorkshire to a mansion in Bristol; from Parliament and Lloyd George’s “coupon election” to the steppes of southern Russia.

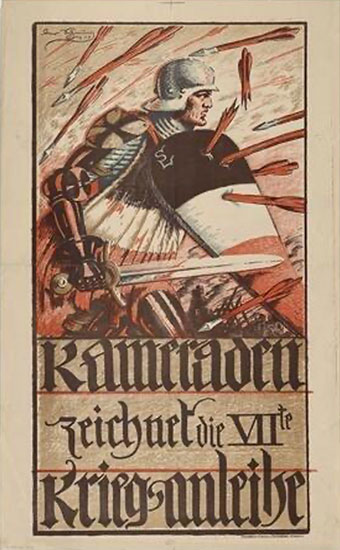

A German poster for war bonds. Translation: Comrades, sign up for the 7th war bond.

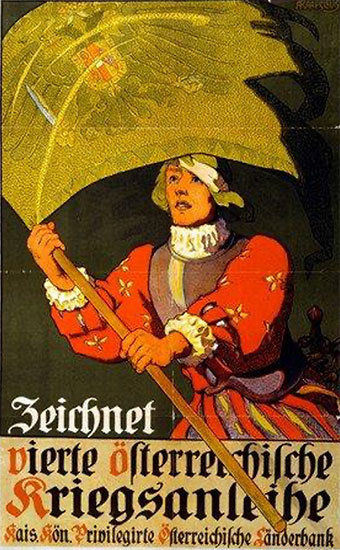

An Austrian poster for war bonds. Note the black double eagle—the symbol of the dual monarchy.

Translation: Sign up for 4th Austrian War Bond. Imperial Austrian States Bank.

Sopwith Pup

This is the first airplane we meet in Changes Wrought. The Pup (officially the Sopwith Scout) became operational in the fall of 1916; most of them were powered by 80 hp Le Rhône rotary engines. The lightweight Pup had excellent high-altitude performance, but its single Vickers machine gun put it at a distinct disadvantage against the German Albatrosses at medium or low altitude. If you’re wondering where the moniker “Pup” came from, the Pup had similar lines as the two-seat Sopwith 1 ½ Strutter, which preceded the Pup into the war by about six months. As the new Sopwith Scout was seen as the offspring of the larger 1 ½ Strutter, someone christened it the Pup, and the name stuck.

BE2

The BE2 was operational before war broke out and was an outstanding reconnaissance aircraft early in the war. By the end of 1915 most of the early BE2s models had been returned to training squadrons in England.

The photo is of a BE2c, which appeared on the continent in early 1915, and was used for reconnaissance, artillery spotting, and as a (very) light bomber. The BE2’s performance was lackluster compared to newer aircraft, and while its inherent stability made it easy to fly, it also meant the aircraft was relatively unmaneuverable. The BE2 was outclassed by the Fokker Eindecker with its single forward-firing machine gun, and even more so by the early-model Albatrosses and Halberstadts. As a result, some British pilots christened their BE2s as “Fokker Fodder.”

The BE2 was unusual in that the pilot sat in the rear seat while the observer sat in the front seat. It’s clear the observer had a restricted field of fire for his Lewis gun, and at times would need to contort himself into a firing position, while being careful not to be tossed overboard (the British did not issue parachutes to their aircrew in WW1).

Sopwith Camel

Along with the Fokker Triplane, the Camel was one of the two most famous airplanes of WW1. It was highly maneuverable, which was wonderful for experienced pilots in combat but also resulted in numerous crashes in training. All Camels had rotary engines; most of them 130 hp French Clergets (many of these built under license in Britain). However, the performance of the Clerget 130 dropped off rapidly above 12,000 feet or so, and they were gradually replaced by Le Rhône 110s and Clerget 140s in the front-line squadrons. The Camel was armed with twin Vickers machine guns and got its name from the hump in front of the pilot that encased the guns.

Captain Roy Brown, flying a 209 Squadron Sopwith Camel, was officially credited with shooting down Manfred von Ritchofen on 21 April 1918, although later research indicates it is more likely the fatal bullet was fired by a machine gunner on the ground.

SE5a

The SE5a first appeared on the Western Front in April of 1917. This is Ian Crosse’s airplane throughout most of CW, and Pete Newin chases down a Gotha bomber in an SE5 at night in Book Four.

The SE5 was fast and had excellent high-altitude capability. It was armed with a synchronized Vickers and an overwing Lewis gun firing above the propeller arc. The ammo drum of the Lewis could be changed in flight, even in the middle of a dogfight if one was adept enough.

Albert Ball was the first of many famous SE5 pilots. One technique he used was to sneak up on his victim from below and behind, with his Lewis gun angled about 45 degrees up. He would close to point-blank range and fire, without any of the normal combat maneuvering.

Bristol Fighter

Along with the Camel and the SE5a, the Bristol Fighter made up the “Big Three” of the capable, late-war British fighters. It was designed and built by the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company (“British” or “Bristol” for short). Armed with a forward firing Vickers and a Lewis gun for the observer, the Fighter was an excellent all-purpose aircraft and could hold its own against the best German single-seat fighters.

Ian Crosse is from the Bristol area and is planning a run for Parliament after the war. He makes the acquaintance of the Chairman of Bristol while setting his sights on the oldest daughter.

After flight training, Harry Booth flies the Fighter in Books Four and Five.

DH9 / DH9A

The DH9 was a capable two-seat light bomber. We meet the forerunner of the “Nine” in Book Three—the always colorful Drew Harris is a flight commander in the DH4. Whether the Nine was much of an improvement over the Four is debatable, but its tighter cockpit arrangement allowed for better communication between the pilot and the observer.

We get to know the Nine well in Book Five of CW, as Pete and Drew prepare to fly a rather improbable mission in southern Russia. Their Nines are powered by 400 hp U.S. Liberty V-12s. Most of the kinks in that engine had been worked out by 1919.

Albatros D V

The Albatros D III and D V were the workhorses of the German single-seat fighters. Very capable airplanes, although somewhat outclassed by the newer Allied fighters in the latter stages of the war. The Albatros is easily recognized by its rounded nose and the “V” arrangement of its wing struts—leading to the moniker “V-Strutter.”

This shot is of a D V. Its fuselage is more rounded than that of the D III, although the performance of the two airplanes was similar. Both were armed with dual eight-millimeter machine guns. The fuselage was constructed of plywood, whereas most British airplanes used fabric over a wooden or metal frame.

The Triplanes

A Fokker pursuing a Sopwith. Mark Newin is puzzling over triplane aerodynamics when we meet him at the National Physical Laboratory in Book One. The Sopwith Triplane was flown by Royal Navy pilots on the continent early in the war. Although many pilots believed three wings increased climb and turn rates, this was ultimately shown not to be the case.

The Sopwith Triplane had a larger wingspan and was heavier than the more famous Fokker Triplane. The Sopwith was reasonably capable despite its single Vickers machine gun, although it was not in the same class of the later British fighters. Despite its modest performance, the Sopwith was the initial impetus behind the Fokker Triplane.

The Fokker had excellent climb and turn capability but was relatively slow. Interestingly, some Fokker Triplanes were powered by French Le Rhône rotary engines (taken off downed Allied aircraft).

Fokker D VII

The Fokker D VII did not appear on the Western Front until the spring of 1918. The D VII was armed with dual Spandau eight-millimeter machine guns and was powered by a water-cooled inline six-cylinder engine. The early models had a 160 hp Mercedes, which was later upgraded to a 185 hp BMW. The aircraft was a very capable dogfighter, and the 1918 armistice agreement specified all D VIIs were to be handed over to the Allies.

The Books

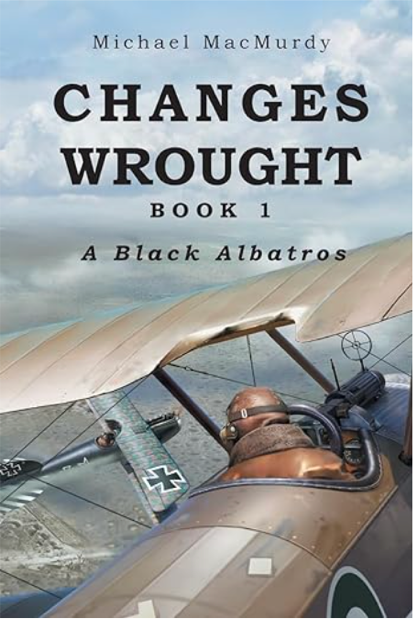

Changes Wrought

— Book One

He lit a cigarette and tossed the burning match onto the table. Set the cigarette on the edge, put his fists down and his chin on his fists. Watched the match burn down, then out. The little blue-gray smoke trail curled up. He flicked the match with his finger and looked at the little burn mark. Felt it. Still warm. His contribution to the table’s character. He straightened up and looked over to the bar …

READ MORE >>

Changes Wrought

— Book Two

The Devonshires held this trench, the Devonshires hold it still.

Pete read the words twice. Ran his fingers over the wood. It was gritty with dirt. He took his scarf out and wiped it off. Traced the words with his finger, the edges still sharp from the chisel. Looked down the row of simple wooden crosses …

READ MORE >>

The Planes

Sopwith Pup

BE2

Sopwith Camel

SE5A

Bristol Fighter

DH9/DH9A

Albatros D V

The Triplanes

Fokker D VII

Allied Vickers Machine Gun

A British belt-fed, water-cooled, eight-millimeter Vickers machine gun. This was the allies standard heavy machine gun during WW1. A lighter air-cooled version was used on most allied aircraft, synchronized to fire through the propeller arc. The Vickers was largely derived from the German Maxim.

British Lewis Gun

A good shot of the famous Lewis gun. This one has the earlier 47-round ammo drum, which was later supplanted by the 97-round “double stacked” drum. The Lewis was used by Allied observers, usually sitting in the back seat of an aircraft, although in some aircraft the Lewis was fixed to fire forward above the propeller arc. Unlike the Vickers, the Lewis could not be synchronized to fire through the propeller arc.

An Australian Lewis gunner may have fired the shot that killed Manfred von Ricthofen.

British 13-pound 9 cwt

anti-aircraft gun

A British 13-pound 9 cwt anti-aircraft gun in action somewhere on the Italian Front. The history behind this weapon is interesting. Before the war the 13-pound field gun (the smaller sibling of the Royal Field Artillery’s 18-pounder) was the standard weapon of the Royal Horse Artillery. Once war broke out it was determined the 13-pounder had sufficient muzzle velocity to serve as an anti-aircraft weapon, whereas the 18-pounder did not. The anti-aircraft version of the 13-pounder was designated the 13-pound 6cwt (6cwt indicating the breech and barrel assembly weighed approximately 600 pounds). In late 1915 the British combined two ideas. They put a liner in the 18-pound gun, reducing its caliber from 3.3” to 3.0”. This allowed the gun to fire the lighter 13-pound shell using the more powerful 18-pound cartridge. The marriage was a success, and the 13-pound 9cwt was produced in large numbers. Unlike the gun shown above, many of the guns were mounted on lorries to increase mobility.

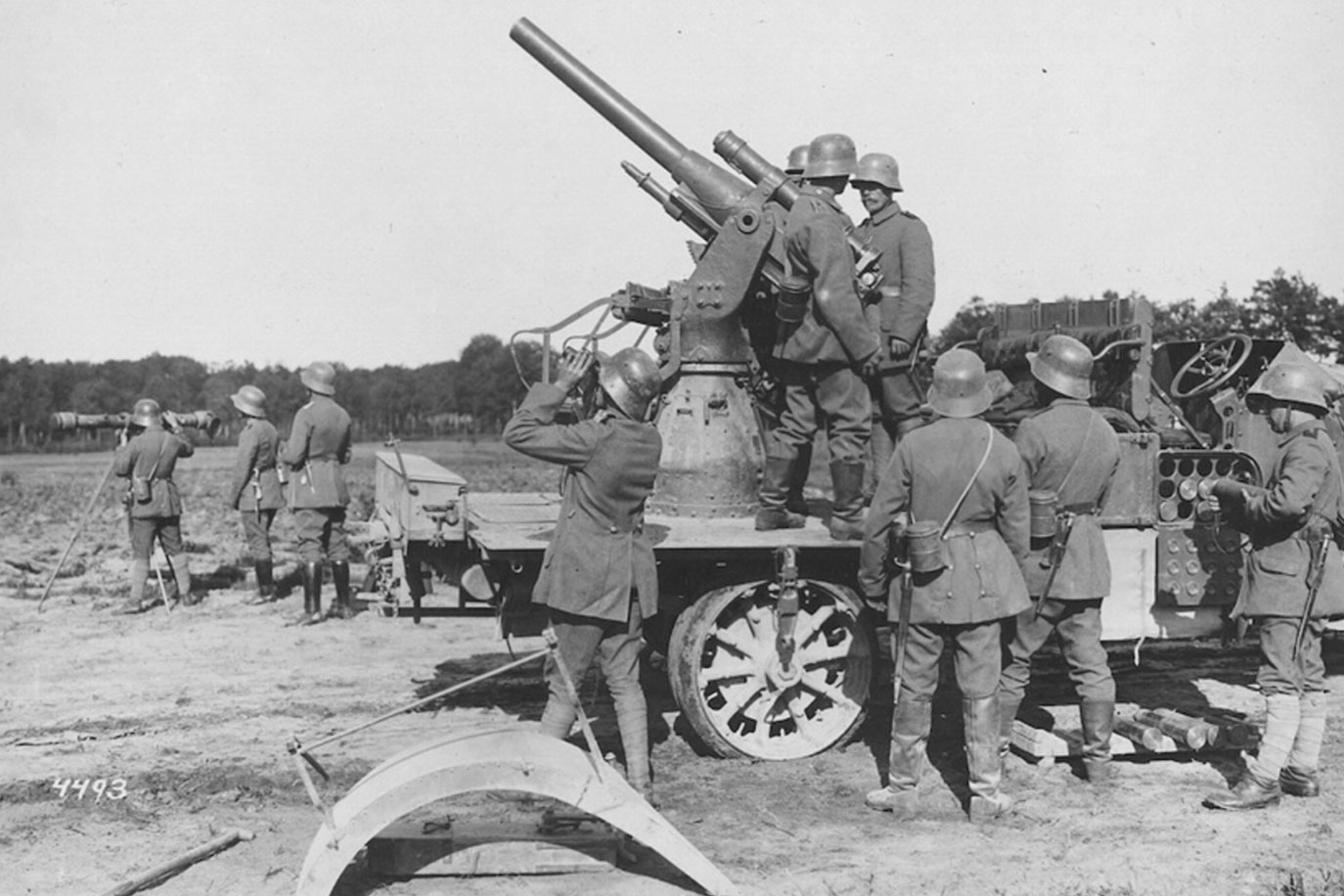

German 7.7 cm Anti-Aircraft Gun

The 7.7 cm gun was the standard German anti-aircraft gun for most of the war, although its muzzle velocity was lowered than desired. The Germans also made extensive use of captured Allied guns in the AAA role. On the left side of the photo, a soldier is operating a stereoscopic rangefinder.

The Germans eventually developed a more powerful 8.8 cm anti-aircraft gun—the forerunner of WW2’s fearsome German 88.

The Guns

Allied Vickers Machine Gun

British Lewis Gun

British 13-Pound 9 CWT

Anti-Aircraft Gun

German 7.7 CM

Anti-Aircraft Gun

The Situation on the Ground

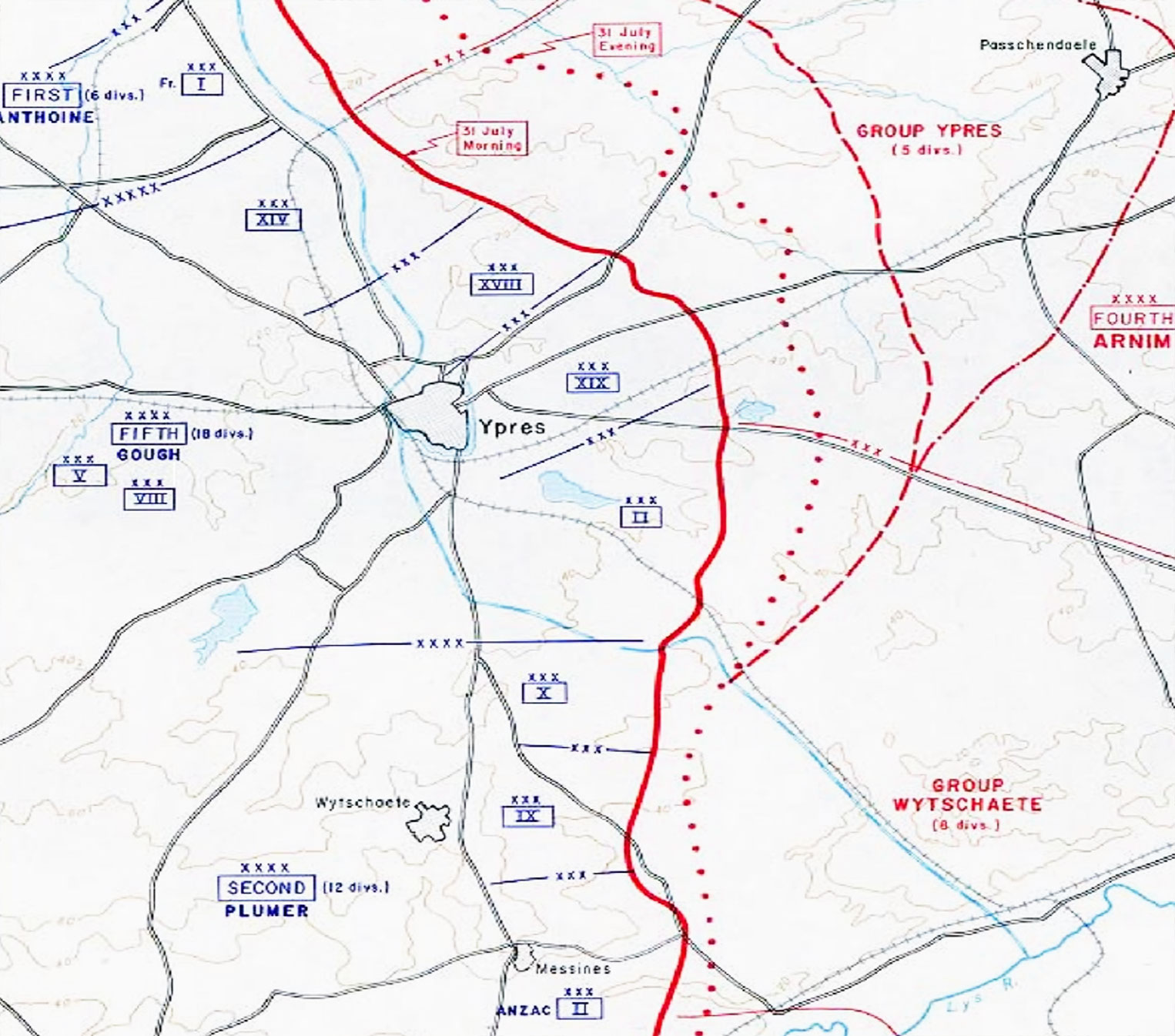

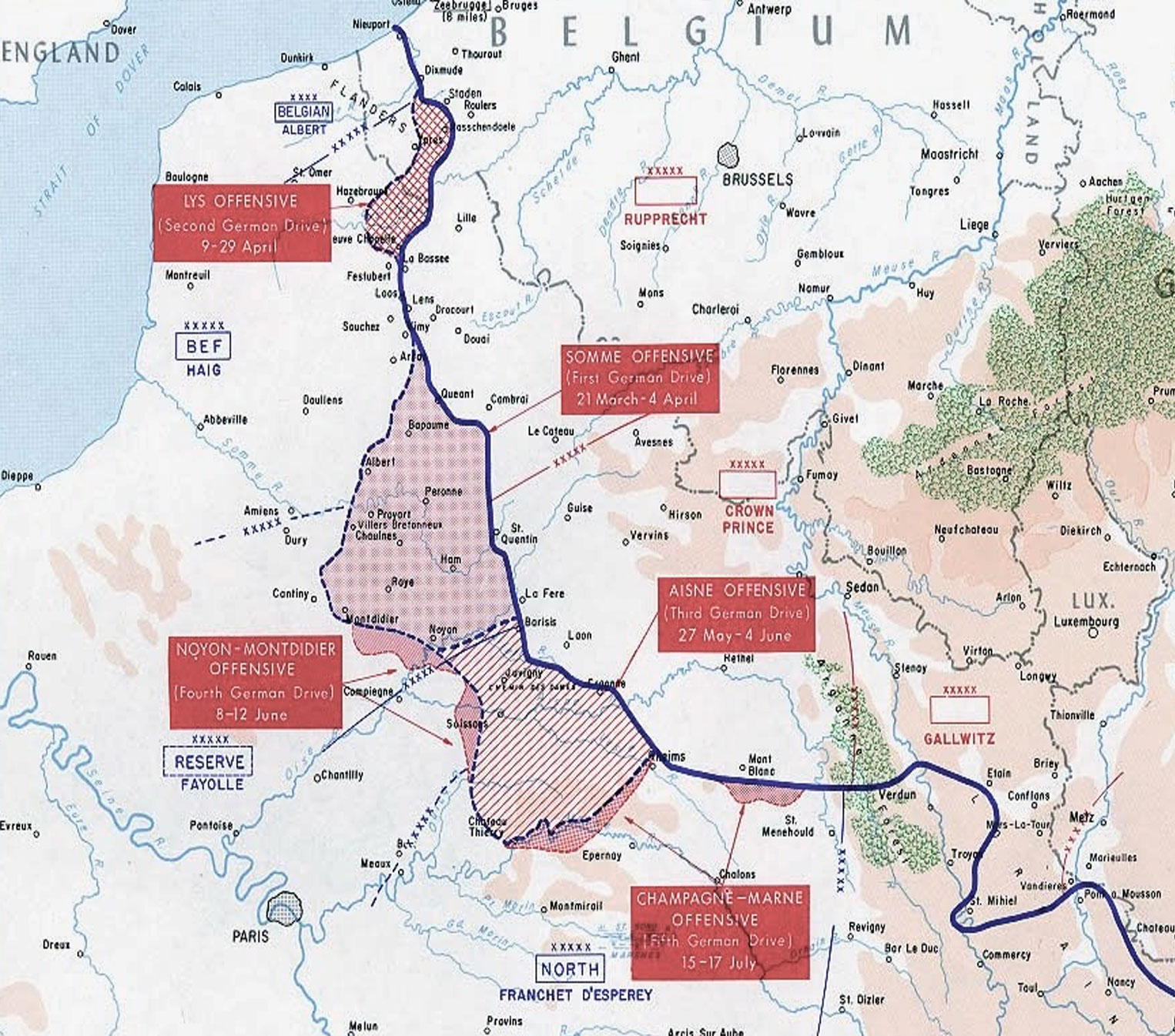

All maps courtesy of the United States Military Academy Department of History

The Stabilized Front

In Book One of Changes Wrought Pete Newin is stationed near Hazebrouck (southeast of Calais) and Harry Booth is a little farther northeast, closer to Ypres. The front line has moved little since the autumn of 1914. The British gained some ground down on the Somme in 1916 at a terrible cost, while the French and the Germans slaughtered each other at Verdun. Now, in the summer of 1917, Field Marshal Haig is readying his troops for a major assault in Flanders.

31 July 1917

Plummer’s Second Army successfully captured Messiness Ridge in June (bottom of map). The British exploded nineteen mines under the German positions—the combined explosions may have been the loudest sound created by man until the arrival of the nuclear age. His right flank secure, Haig is ready to launch his attack, which will drag on for three horrible months.

The British and their allies will suffer around 300,000 casualties in the Third Battle of Ypres, without breaking the German line or capturing the U-Boat bases on the Belgian coast. The very high losses will aggravate the already tense relationship between Lloyd George and his senior generals.

Harry Booth’s first combat flight is a photo recce mission in a BE2 over Messiness Ridge. Harry’s 6 Squadron was attached to X Corps; however he and Jack were on loan to IX Corps that day. About six weeks later Pete Newin crosses the front line near Ypres in his Sopwith to attack a German aerodrome, in the early morning hours of 31 July 1917.

Spring 1918

The Germans transferred approximately fifty divisions to the western front when Russia dropped out of the war, allowing Ludendorff to launch a wave of attacks beginning in March of 1918. As can be seen the stagnated front was shattered and the Germans gained significant ground, but ultimately the Allies held. Lieutenant Mark Newin is in action near the Lys River during the second German offensive in Book Four of CW.

Pete Newin is a flight commander in the Sopwith Camel.

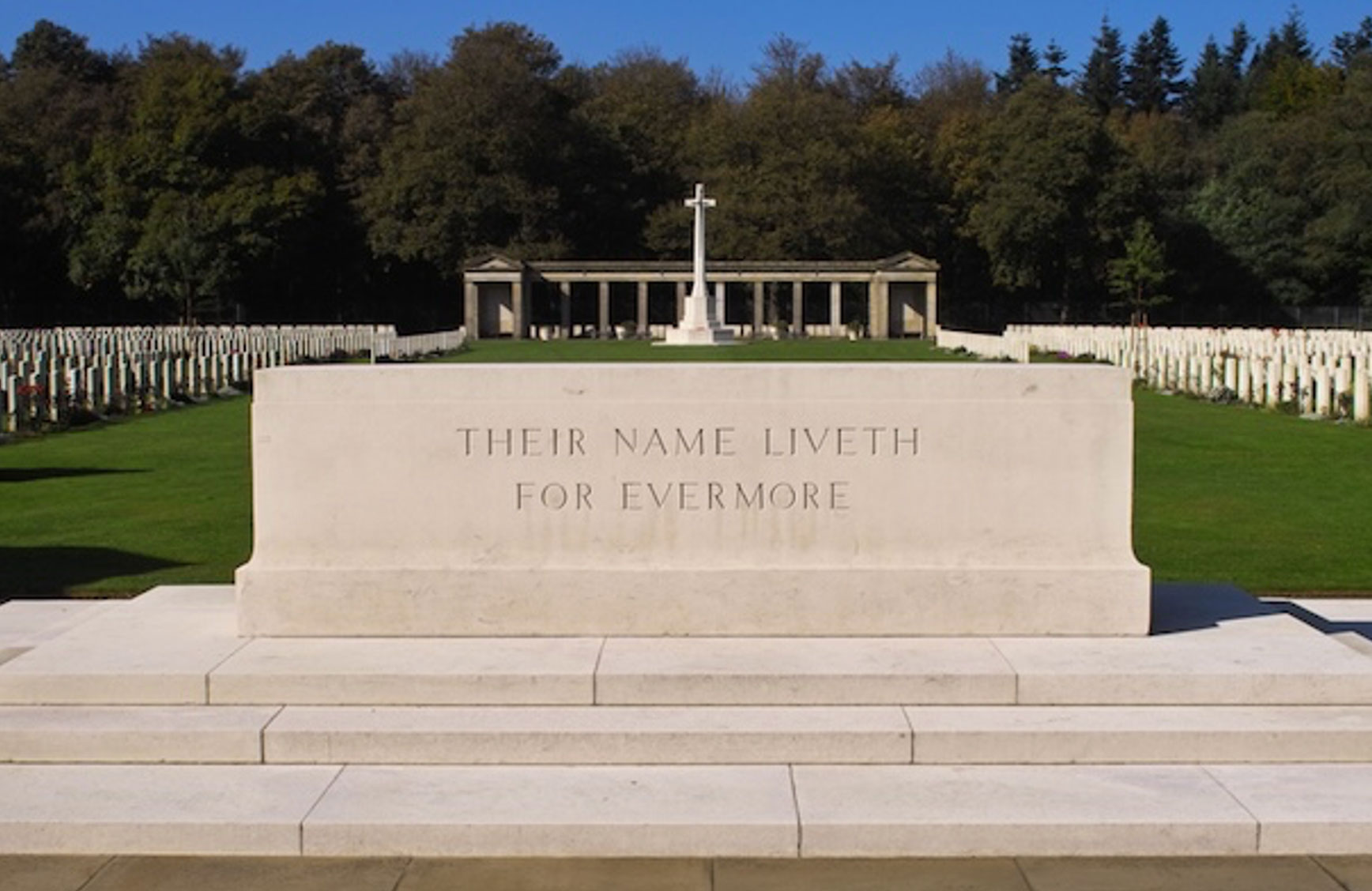

The Devonshires held this trench, the Devonshires hold it still.

Pete read the words twice. Ran his fingers over the wood. It was gritty with dirt. He took his scarf out and wiped it off. Traced the words with his finger, the edges still sharp from the chisel. Looked down the row of simple wooden crosses. The line was straight and the crosses evenly spaced. Like their soldiers that day—lined up to go over the top when the whistle blew. The sun was shining but he was in the shade of a little copse of trees, which would have been just beyond the forward British trenches that morning. But word was hundreds of the 9th Devonshires didn’t even make it this far. That the German artillery had destroyed the forward trenches and the attack started from the British second line.

The cemetery wasn’t large, and not very different from hundreds of others in France and Belgium. One little corner of remembrance, to what history would know as the Battle of the Somme. He stood up and looked across the field, across what would have been no-man’s-land that morning.

Harry Booth is still trying to survive life as an observer in the RE8, while having some fun along the way.

“At ease, lieutenant.” Harry relaxed his posture but remained standing as the corporal closed the door behind him. He looked down at the desk without moving his head—their overweight and balding squadron commander was bent over a letter. He was holding a cigarette in his right hand, and flicked the ash in the general direction of an overflowing ashtray as he read. Harry studied the top of the major’s head. Unlike the more typical, shiny apple sort of spot, the major’s bald spot seemed to absorb the light, like aged parchment. If he poked it with his finger, would it go right through? Pull it out and it’d be sticky red with bits of brain—like a candy stick from the circus? Had he ever seen the major fly an airplane…he didn’t think so. It was probably just as well—the wind might peel the top of his head off and blow it back into the observer’s face. The letter had some sort of legal seal at the top, and Harry winced as he read the upside-down heading: City of Liverpool Police.

“Mister Harry Booth,” the major read. “Twenty-seven Thomson Street. Everton. Liverpool. Would that be you, lieutenant?”

Ian Crosse meets his wife-to-be and her little sister.

“But they are terribly boring, daddy’s parties. All these old fellows talking about business and bye-bye elections and taxes. The latest cure for hemorrhoids. While the wives show off their jewelry and vie to see who can look the most under the age of a hundred. Drop little hints to each other about their young playthings.” She licked her lips and ran her tongue around the edge of her wine glass as her eyes roamed about the room. “Young men off fighting a war is much more interesting. I love hearing stories about horses crashing through the poor enemy soldiers—trampling them down as our heroes slash them with sabers. Fellows flying about in airplanes and shooting people with machine guns. Or do you drop bombs on them?” Her bright blue eyes had settled on him again.

“Machine gun in my case. The Sopwith Pup doesn’t usually carry bombs.”

“Ahh, Sopwith. The enemy. Daddy’s so proud of his Bristol Fighter…

Mark Newin battles his way through army training.

“You’re not cut out for the infantry, private. At least not as a common soldier. But the army has many needs, and one of them is junior officers. Most of the ones we send across don’t last long. And as we all just obey orders around here, pack your kit. You’re leaving in the morning for Officer Cadet Battalion, Penrith. I’d dress warm if I were you. That’s all.”

Mark was stunned. Instead of flunking out of Basic, he was going to an OCB? Bumbling Mark Newin would lead men into combat? Their lives would depend on split second decisions he’d make? This couldn’t be. He stared at the captain, who was lighting his pipe. He opened his mouth to say something. Closed it. Still not knowing what to do or say, he saluted and spun around. Took a couple of uncertain steps, grappling with what he’d just heard.

A voice stopped him as he went out the door. “Mark?”

It took him a few seconds to process that word—no one other than a fellow recruit had called him “Mark” for the last two months. He turned around. The captain was looking out the window, puffing on his pipe. His eyes flicked to Mark. Went back to the window.

“You didn’t do well here, but think about how much you did learn. And I’ll let you in on the British Army’s little secret. You don’t need to know much about warfighting to be a good junior officer. The little bit you need to know, you’ll learn soon enough. It’s not hard. What is important, is to take care of your people. Be tough with the ones that need it; show compassion when it’s warranted. But most of all, lead by example. You do that, if you’re the first one up the ladder when the whistle blows, they’ll follow you. That’s all that matters.”

Lieutenant Pete Newin is a Sopwith Pup fighter pilot.

He lit a cigarette and tossed the burning match onto the table. Set the cigarette on the edge, put his fists down and his chin on his fists. Watched the match burn down, then out. The little blue-gray smoke trail curled up. He flicked the match with his finger and looked at the little burn mark. Felt it. Still warm. His contribution to the table’s character. He straightened up and looked over to the bar. The old heads, somber. The newer chaps louder, their arms around each other now and again. Hands flying about—refighting air combats with alcohol-reinforced vigor. The occasional song or argument.

The bartender set up another row of whisky glasses and filled them. Alcohol—one constant of existence in the Royal Flying Corps. Along with cigarettes and castor oil. Diarrhea. Dead pilots and new pilots. Drawn from Britain’s inexhaustible supply of young men.

He pushed his cigarette to the middle of the table. Flicked the end of it and watched it make little red circles as it spun to the floor. Like an airplane going down in flames. He ran his eyes across the tabletop again. There was a tiny, sharp gouge he hadn’t noticed before; the wood was gray where the point had chipped the finish away. Someone had stabbed his knife into the table years before. Had the knife passed through a hand on its downward plunge? More cheating at cards? If he had a microscope, could he see tiny bits of blood and flesh in the hole? Or had the evidence long since been washed away?

Lieutenant Harry Booth is a Liverpudlian fabric store kid turned RFC observer.

Okay, Harry, we can’t stay here. Another push and pull, and another few inches of progress through the sticky mud. Another deep breath, and on the third try, he made it out. Pulled himself onto a knee and looked around, his heart pounding. The visibility had been rotten all day, but right there it had to be at least five miles, and a Hun observation balloon was visible below the clouds. What was it that West Country corporal had said? “We don’t like you chaps crashing nearby. Brings the Hun artillery.”

He looked toward the nearest British trenches, but no one was rushing to their rescue. Looked at the Hun balloon again. Maybe if he gave them a friendly wave? Surrendered? He crawled to the forward cockpit and looked at Norman. His eyes were alert and he was breathing, but he didn’t give any sign of trying to get out of there. There was space between the railing and the mud; he should be able to pull him out. He fumbled with Norman’s safety belt and got it undone. Grabbed hold of him as the first shell hit, which answered the question if a beat-up RE8 was worth shooting at.

The shell landed a few hundred yards short, but was big enough and close enough to rattle the airplane. Likely a seventy-seven. But whatever it was, they needed to get the hell out of there.

Mark Newin is a civilian scientist with an approved exemption from military service.

The whistle blows and Private Mark Newin climbs out of the trench. Charges forward, bayonet fixed. An artillery shell bursts to his right, knocking one mate down. To his left, the Hun machine-gun fire cuts down two more. A bullet slices through his side, he staggers and drops to a knee. Gasps for air…pushes himself onto his feet and keeps going forward. The barbed wire tears at his hands and face, but he fights his way through and jumps into the first German trench. Fires from the hip, bringing a Hun down. Lunges forward with his rifle, just in time to knock aside the plunging bayonet of another, saving his best friend’s life.

And that was about as unlikely a scene as he could possibly conjure up. Twenty-eight-year-old, overweight and out-of-shape Mark Newin, who had never fired a gun in his life—the war hero. If he put this in ledger form, it wouldn’t be a close call. He could do far more good at the Lab than he could trying to play army. But there’d be that one nagging footnote on the “Stay at the Lab” side of the Mark Newin ledger. Had he stayed at the Lab because he was afraid?

FAQs

1. Why did you choose to write about WW1 aviation?

First, to make people aware of how rudimentary WW1 aircraft were: open cockpit, very little instrumentation, unprotected fuel tanks. Second, to highlight that these aircraft did far more than fly around and dogfight each other. Both the artillery spotting and photo reconnaissance missions, while less “glamorous” than air-to-air combat, were critical to the war effort.

2. What is the significance of the title “Changes Wrought?”

This refers to the great changes technology brought to WW1: aircraft, powerful and accurate artillery fire, machine guns, and the relative unimportance of cavalry.

3. You can be very critical of Sir Douglas Haig. Do you believe he was a poor general?

There are strong feelings on this issue from both sides. Oddly enough, of all the things I’ve read on this, the person I thought nailed it best was a professor of English. Paul Fussell wrote the wonderful “The Great War and Modern Memory,” which looks at WW1 through a literary lens. This is what Professor Fussell had to say about Field Marshal Haig:

One doesn’t want to be too hard on Haig, who doubtless did all he could and who has been well calumniated already. But it must be said … in a situation demanding the military equivalent of wit and invention. Haig had none. He was stubborn, self-righteous, inflexible, intolerant—especially of the French—and quite humorless. … Bullheaded as he was, he was the perfect commander for an enterprise committed to endless abortive assaulting.

To answer the question, I believe it wasn’t so much that Haig was a bad general, rather that the nature of warfare had fundamentally changed and he was not able to adapt to the new reality.

4. What exactly is a rotary engine?

Rotary engines are similar in appearance to the radial engines that were used in some WW2 fighters, in that the cylinders project outward from a central shaft (the photo is of a nine-cylinder Le Rhône rotary mounted on a Sopwith Pup). The difference is the entire cylinder assembly of a rotary engine is fixed to (and rotates with) the propeller. This allows the engine to be air-cooled, saving weight and design complexity. The primary drawback is the spinning propeller and cylinder assembly effectively acts as a big gyroscope at the front of a small, lightweight aircraft.

Viewed from the cockpit, the cylinder assembly is spinning clockwise. Now consider a rotary-engined aircraft in a hard right turn. The turning motion produces a force on the left side of the engine, making it turn (pivot) to the right. A force applied to a gyroscope is “felt ninety degrees of rotation later.” Therefore, the force of the right turn is applied at the top of the gyroscope, pushing the nose of the aircraft down. This effect was more pronounced in some airplanes than others. The most famous example is the Sopwith Camel—new Camel pilots were advised against making right turns at low altitude.

5. What can we look forward to in the later books?

Without giving too much away, Harry Booth runs into problems back in England, centering on a girl, his (former?) best friend, and the Irish Republican Brotherhood. Mark Newin fumbles his way into the army and Ian Crosse pushes ahead with his political plans, all of which may be destroyed by his fondness for his wife’s little sister. Pete and Anya end up in southern Russia after the war, the latter finding herself in a difficult situation.

6. What is the planned release schedule?

usaf student pilot

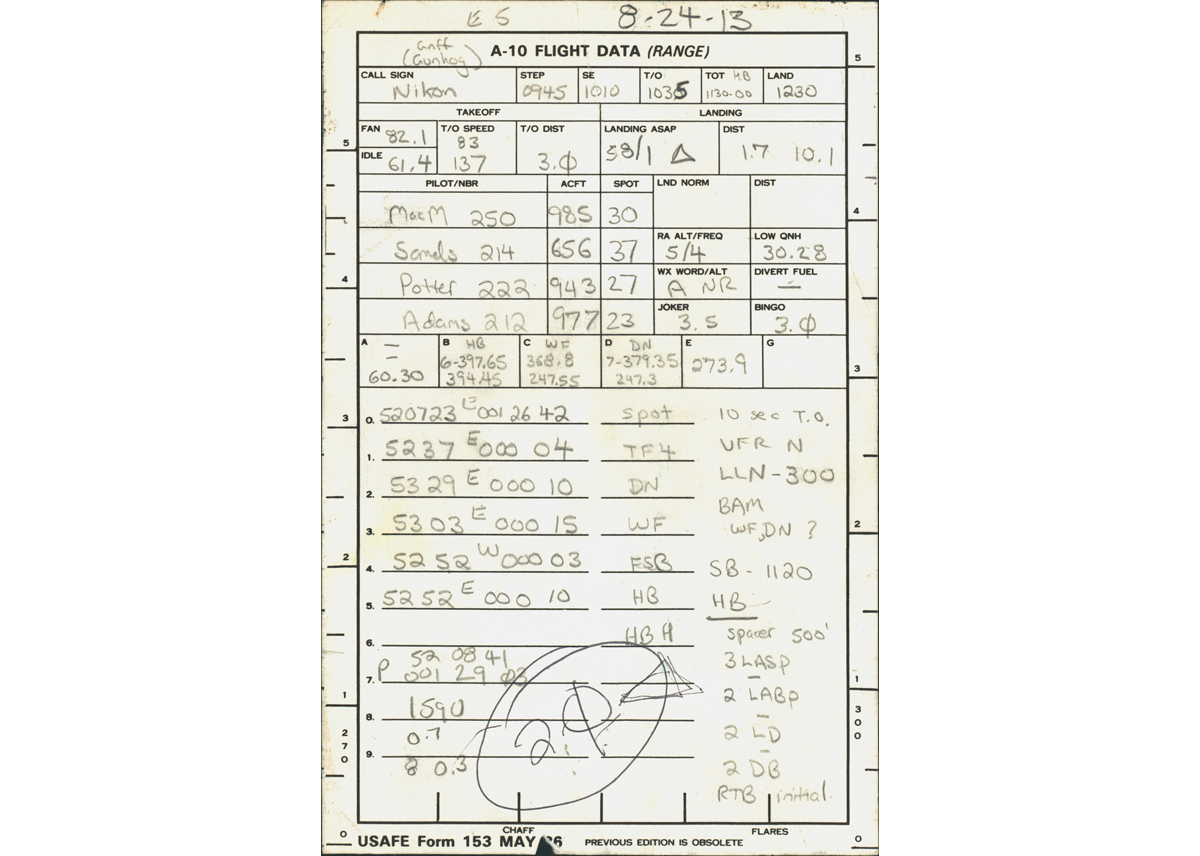

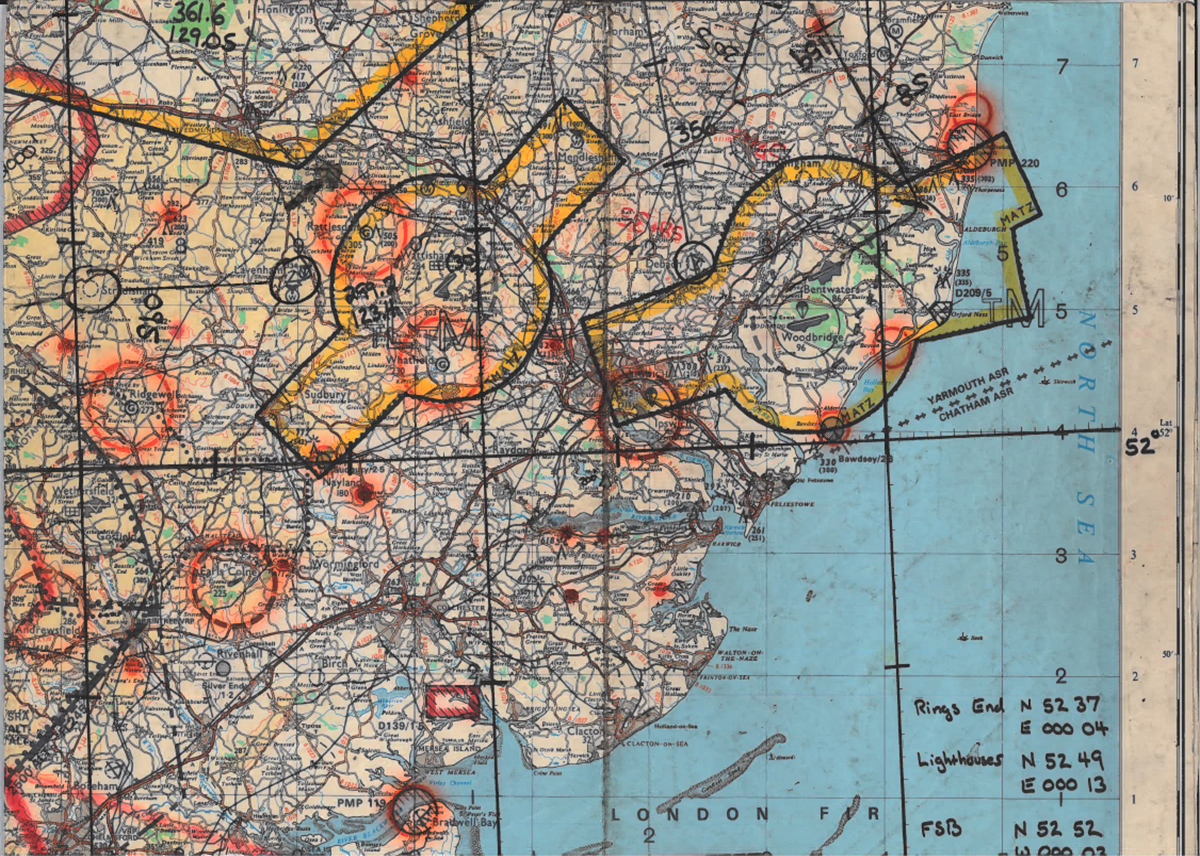

A-10 raf bentwaters

Tail-Dragger Flying

American Airlines

Stearman Flight Training

This is what the entry into a spin looks like. We pull the nose up and reduce power to idle. The airplane runs out of speed and the nose drops. We have full rudder in so that causes the spin. To recover: recheck the throttle at idle. Neutralize the ailerons and apply rudder opposite to the spin direction. Bring the column forward as necessary to break the stall. Once the spinning stops, neutralize the rudder and recover from the dive.

This is your basic traffic pattern and landing onto a grass strip. The final approach is very steep by airline pilot standards, due to the high drag of the Stearman. It’s easier to land on grass—more forgiving of yaw inputs than is a concrete runway.

Contact

For Media & Press Inquiries

Follow on Social Media